Understanding Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Your Questions Answered

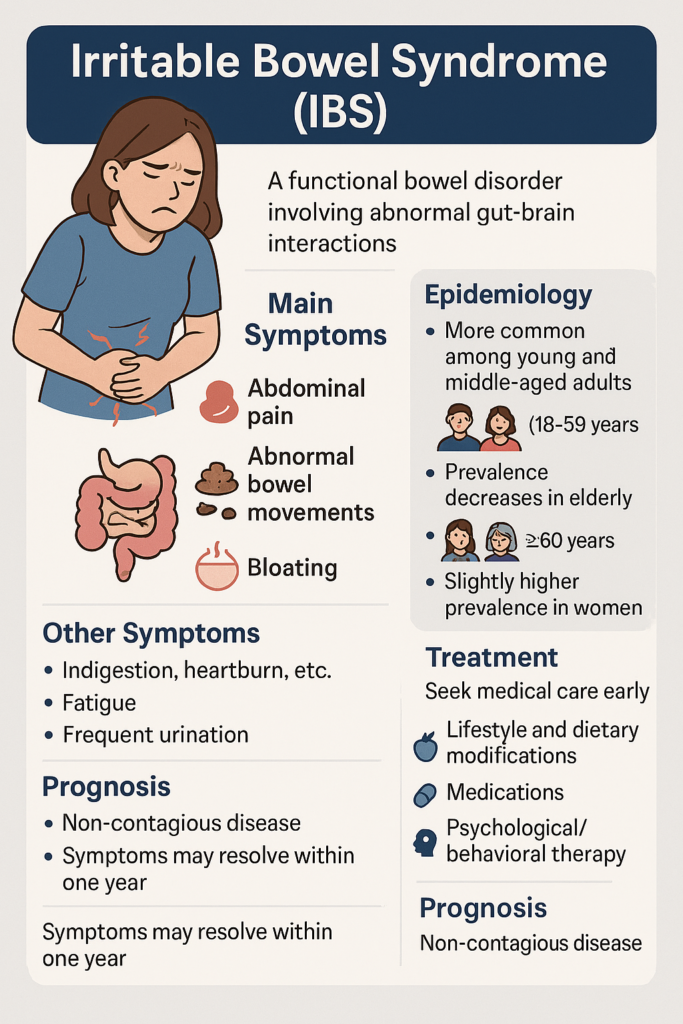

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a functional bowel disorder often triggered by various factors that lead to abnormal interactions between the gut and the brain. Its main symptoms are: abdominal pain, abnormal bowel movements, with changes in frequency and/or stool characteristics. Common types include diarrhea-predominant, constipation-predominant, mixed, and unspecified. It can occur in people of all ages but is more common among young and middle-aged adults (18-59 years), with prevalence decreasing in the elderly (≥60 years). Prevalence is slightly higher in women compared to men.

Symptoms are not constant but may include bloating. Abdominal pain usually occurs in the lower abdomen, is crampy and shifting, and often relieves after passing gas or having a bowel movement. Additionally, it may be accompanied by upper gastrointestinal symptoms like indigestion, heartburn, vomiting; or extra-intestinal symptoms such as fatigue, frequent urination, urinary urgency, and dysmenorrhea. IBS is a non-contagious disease. Based on the actual condition and symptoms, you should seek medical care early.

Treatment for IBS mainly aims to improve symptoms, enhance patients’ quality of life, and eliminate concerns. Primary treatments include lifestyle and dietary modifications, medications, and psychological/behavioral therapy. The specific treatment is formulated by the doctor according to the individual patient’s condition, creating a personalized comprehensive treatment strategy.

Although IBS is long-lasting and recurrent, the overall prognosis is relatively good, with most patients experiencing symptom resolution within one year. Patients with severe psychiatric disorders, a long disease course, or prior surgeries have a poorer prognosis.

The causes and mechanisms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) are not well understood and are currently believed to be the result of multi-factorial interactions causing abnormal gut-brain axis reactions.

Studies show that dietary factors (including immune-mediated, i.e., food allergy, and non-immune-mediated, i.e., food intolerance) can trigger or worsen patients’ symptoms, and gut infections are a risk factor for developing the condition.

Causes

- Visceral Hypersensitivity: IBS patients have significantly lower pain thresholds for colon and rectal distension compared to normal individuals and are more prone to bloating, abdominal pain, and other symptoms. Visceral hypersensitivity is a fundamental cause of IBS, playing an important role in the occurrence and development of the disease.

- Abnormal Gastrointestinal Motility: IBS patients experience increased or decreased digestive motility, or spasms. They are hyper-reactive to stimuli such as eating, intestinal lumen distension, intestinal contents, and some digestive hormones, suffering from frequent attacks. Abnormal GI motility is an important pathogenetic cause, but motility changes differ among IBS patients of different subtypes.

- Neurological Abnormalities: IBS patients have pelvic floor dyssynergia and central nervous system (CNS) disturbances. This can be considered hypersensitivity of the brain-gut axis, involving the enteric nervous system and the central nervous system.

- Psychological Factors: Emotions like anxiety, depression, and chronic stress can affect bowel function via the brain-gut axis, leading to dysmotility (spasms or slowing); approximately 30%-50% of patients have concomitant psychological issues, forming a vicious cycle of “emotion-gut” interaction.

- Neurotransmitter Imbalance: Serotonin (5-HT) is a key neurotransmitter regulating bowel motility and sensation. IBS patients have abnormal levels of 5-HT in the intestinal mucosa (increased in diarrhea, decreased in constipation), leading to motility disorders.

- Gut Infections: Increasing clinical studies show that IBS may be an outcome of acute and chronic infectious gastroenteritis, with its onset linked to the severity of the infection and timing of antibiotic use.

- Gut Microbiome Imbalance: Studies show that diarrhea-predominant IBS patients have significantly reduced numbers of Lactobacillus, Firmicutes, and Bifidobacteria, while Bacteroidetes are reduced. Constipation-predominant IBS patients show increased Verrucomicrobia.

- Imbalance in the gut microecology plays an important role in pathogenesis.

- Changes in Microbiota Composition: The diversity and abundance of gut flora in IBS patients are lower than in healthy individuals. There are specific predominant species in different subtypes – e.g., reduced Dorea sp. CAG:317 and other short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) producers; increased Akkermansia muciniphila in constipation patients. The number of beneficial bacteria (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) decreases, affecting gut balance.

- Effects of Metabolites: Acetic acid, butyric acid, and other SCFAs produced by gut flora metabolism are key substances regulating gut balance, affecting motility, barrier function, and immune response. Abnormal SCFA levels in IBS patients show weaker correlation with microbiota compared to healthy individuals. Diarrhea patients often have bile acid malabsorption, worsening diarrhea symptoms.

- Mechanisms of Action: Flora can affect symptoms through the epithelial barrier (increased intestinal permeability), mucosal immunity (activating inflammatory factors like TNF-α, IL-17), and brain-gut signaling (signal transmission via neurotransmitters/metabolites).

- Psychosomatic Disorders: Numerous studies show that IBS patients often have concomitant anxiety, depression, and other manifestations. Additionally, acute and chronic stress events like unemployment, bereavement, sexual assault, physical punishment, etc., can cause or worsen symptoms.

Predisposing Factors

Gastroenteritis, food intolerance, chronic stress, surgery, and certain medications are the main factors that can cause or worsen symptoms.

The onset of IBS primarily involves abdominal pain and abnormal bowel movements, which are chronic, recurrent, and intermittent.

Typical Symptoms

- Abdominal Pain: More common in the lower abdomen. The pain may vary in location and is unlikely to occur at night. Attacks and their duration are irregular and often relieved after passing gas or a bowel movement.

- Diarrhea: Persistent or intermittent diarrhea with small, loose, or mushy stools, often with mucus, usually without blood. Most episodes occur in the morning or after meals, typically not exceeding 10 times per day.

- Constipation: Often accompanied by a feeling of incomplete evacuation. Diarrhea and constipation may alternate.

Most patients are generally in good health, with abdominal tenderness, spasms, and anal pain during digital rectal examination.

Associated Symptoms

- Upper GI Symptoms: Such as indigestion, heartburn, reflux, etc.

- Extra-intestinal Symptoms: Such as fatigue, frequent urination, urgency, dysmenorrhea, etc.

- Incomplete Evacuation: Patients often feel a “sense of incomplete bowel movement,” related to increased gut sensitivity (visceral hypersensitivity), meaning the gut overreacts to normal stimuli like stool.

Clinical Subtyping (Rome IV Criteria)

Based on the predominant bowel habits over the last three months, IBS is divided into four subtypes:

- Diarrhea-predominant (IBS-D): Diarrhea ≥3 days/week and constipation days <1 day/week.

- Constipation-predominant (IBS-C): Constipation ≥3 days/week and diarrhea days <1 day/week.

- Mixed (IBS-M): Diarrhea ≥2 days/week and constipation ≥2 days/week.

- Unspecified (IBS-U): Symptoms do not match any of the above subtypes.

When to Seek Medical Care

When the following symptoms are recurrent, patients should go to the hospital for appropriate examinations in a timely manner.

- Abnormal bowel frequency (>3 times/day or <3 times/week);

- Abnormal stool form (lumpy/hard or watery);

- Abnormal defecation process (straining, urgency, incomplete evacuation);

- Passage of mucus with stool;

- Abdominal bloating or feeling of distension.

Diagnostic Basis

Diagnosis can refer to Rome IV criteria: Recurrent abdominal pain, on average, at least 1 day/week in the last 3 months, associated with two or more of the following, in the absence of explanatory structural or biochemical abnormalities:

- Related to defecation;

- Associated with a change in frequency of stool;

- Associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.

Symptoms must have started at least 6 months prior to diagnosis, and the above diagnostic criteria must be met for the last 3 months.

Diagnostic Process

- When IBS is suspected based on relevant GI symptoms, a Gastroenterology consultation should be sought as soon as possible.

- The doctor will conduct a detailed consultation, including medical history: GI symptoms; age and time of onset; potential associated symptoms, patient’s psychological state; past GI history and prior treatments, surgical history; systemic history, surgical history, infectious disease history; family history of GI diseases and medication history.

- Patients with “alarm signs/symptoms” should undergo necessary examinations immediately to rule out organic disease. “Alarm signs” are:

- New onset of symptoms over age 40;

- Recent unintentional weight loss >3 kg;

- Anemia, hematemesis, or melena (black stool);

- Jaundice;

- Fever;

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing);

- Abdominal mass;

- Symptoms progressively worsening.

Patients with psychological/psychiatric disorders should also be evaluated over time. IBS is diagnosed after targeted exclusion of other organic diseases.

- The doctor assesses the severity of the patient’s condition and their willingness to undergo appropriate treatment.

Relevant Examinations

- Imaging Tests:

- Colonoscopy: Recommended for patients with the above “alarm signs,” those with a family history of colorectal cancer, patients over 40 with recent changes in bowel frequency/stool characteristics, or progressive worsening of symptoms, to rule out organic lesions. Requires fasting.

- Abdominal CT Scan, Abdominal Ultrasound: Performed if necessary; both require fasting.

- Laboratory Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC), Urinalysis, Stool Routine: Basic tests for outpatients and inpatients. A 12-hour fast is required before CBC. Avoid fatty foods the night before. For urinalysis, collect a mid-stream sample; women should avoid the period 3 days before and after menstruation. For stool tests, avoid blood-containing products (like rare meat) 3 days prior; a light, easily digestible diet the day before is advised, along with adequate sleep.

- Blood Chemistry, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR), Liver Function Tests: Performed if necessary. Main tests include blood glucose, creatinine, and thyroid function.

- Etiological Examination: Stool samples should be collected early in the illness, before starting antimicrobial therapy, and examined immediately after defecation. Sample pus, blood, and soft/watery parts. Keep warm during transport and examination in cold weather.

Differential Diagnosis

IBS is often associated with functional dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), occurring simultaneously. Attention should be paid during diagnosis to avoid missed diagnoses.

Additionally, it often needs differentiation from the following conditions:

| Condition | Key Identifying Features |

|---|---|

| Chronic Bacterial Infection | Confirmed by multiple positive stool routine/culture results, with significant symptom improvement after adequate systemic antibiotic therapy. |

| Malabsorption Syndrome | Presents with diarrhea, but stool often contains fat and undigested food. |

| Colorectal Tumors | Symptoms can mimic functional bowel disorders like diarrhea/constipation, especially in the elderly. Barium enema or colonoscopy can confirm. |

| Ulcerative Colitis | Accompanied by fever, bloody stool, etc. Identifiable by imaging or colonoscopy. |

| Thyroid Disorders | Hyperthyroidism can cause diarrhea; hypothyroidism can cause constipation. Thyroid and parathyroid function tests can differentiate. |

| Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS) | Symptoms (diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue) triggered by gluten intake, heavily overlapping with IBS. High prevalence in treatment-resistant IBS. Differentiated by Salerno Experts’ Criteria and a gluten-free diet trial. |

| Carcinoid Syndrome | Caused by bioactive substance (e.g., serotonin) secretion by neuroendocrine tumors, accompanied by the triad “abdominal pain + diarrhea + flushing.” Elevated serum serotonin/urinary 5-HIAA; tumors detectable on imaging. |

| Crohn’s Disease | Organic disease visible endoscopically (ulcers, strictures, cobblestoning). Biopsy shows non-caseating granulomas. About one-third of patients in remission have IBS-like symptoms and should be evaluated concurrently. |

| Other Conditions | Celiac disease (positive anti-gliadin antibodies, small bowel villous atrophy), Microscopic colitis (biopsy shows inflammatory cell infiltration into lamina propria), etc. |

Treatment

Treatment for IBS focuses on improving symptoms, enhancing patient quality of life, and alleviating concerns. It mainly includes general measures, medication, psychotherapy, and behavioral therapy. Specifically, doctors develop individualized comprehensive treatment strategies based on the patient’s condition.

General Treatment

Identify and try to remove triggering factors; guide patients to establish good lifestyle and dietary habits, avoiding foods that trigger symptoms. Educate the patient about the nature of IBS to alleviate concerns. Sedatives may be appropriately given for those with insomnia and anxiety.

Medication

| Category | Function & Examples |

|---|---|

| Antispasmodics | Improve overall symptoms in diarrhea patients, significant effect on relieving abdominal pain. Includes anticholinergics (e.g., scopolamine), smooth muscle relaxants (e.g., mebeverine, alverine), gut-selective calcium channel blockers (e.g., pinaverium bromide, otilonium bromide), and peripheral opioid receptor agonists/antagonists (e.g., trimebutine). Anticholinergics should be used short-term. |

| Antidiarrheals | Improve diarrhea symptoms. Loperamide slows intestinal transit, enhances water/electrolyte absorption. Diphenoxylate/atropine combination, adsorbent smectite are also effective. |

| Laxatives | Generally, mild-acting laxatives are recommended to reduce side effects. |

| Visceral Analgesics / 5-HT Modulators | 5-HT has multiple effects on peripheral smooth muscle, secretion, and nerves. The 5-HT3 receptor antagonist alosetron can relieve pain, urgency, frequency in women with IBS-D, but caution is needed for side effects like ischemic colitis. |

| Psychotropic Drugs | Alleviate symptoms in moderate-to-severe IBS patients with psychological issues. Antidepressants may also be given for non-psychiatric patients when other drugs are ineffective. |

| Gut Flora Interventions | Includes probiotics, prebiotics, and rifaximin. |

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

TCM believes liver depression and spleen deficiency are important etiologies for IBS. Combining disease and syndrome differentiation, TCM can compensate for shortcomings of modern medicine in treating refractory IBS and patients with anxiety/depression, reduce long-term Western medicine side effects, and has unique advantages in comprehensive treatment.

Other Therapies

- Dietary Therapy: Western scientists found a link between specific carbohydrate intake and IBS. An elimination diet (e.g., low FODMAP) can identify trigger foods, forming the basis for an individual diet plan.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helps patients identify triggers (e.g., stress, diet), learn coping skills (cognitive restructuring, relaxation training), reducing symptom frequency/severity.

- Stress Management: Reduces sympathetic arousal via meditation, yoga, deep breathing, etc.

- Exercise Therapy: Moderate aerobic exercise (walking, running, yoga) improves bowel movements and regulates mood.

Epidemiology

IBS is one of the most common functional GI disorders globally, with a prevalence of approximately 4%-9% worldwide, higher (10%-15%) in developed nations due to lifestyle factors. The most affected group is young and middle-aged adults (18-59 years). Women have about twice the risk of men. Symptoms usually start before age 45. The disease course is chronic, often triggered or worsened by diet, mood, or other factors.

Prognosis & Prevention

Prognosis

Although the IBS course is long and recurrent, the overall prognosis is generally good, with symptoms resolving for most patients within one year.

Patients with persistent abdominal symptoms have a poorer prognosis, with about 5%-30% still symptomatic after 5 years.

Patients with severe psychiatric disorders, long disease course, or prior surgical history show a poorer prognosis.

Severity

IBS can seriously affect patients’ quality of life, impacting work, study, daily life, and mental health.

- Unified Treatment: Take medication as advised by a doctor; avoid self-discontinuation/abuse.

- Lifestyle: Adjust diet (avoid trigger foods), maintain a good psychological state.

- Symptom Management: Use “food-symptom” diaries to reduce attack frequency.

Prevention - Dietary Modifications: Avoid gas-producing foods (beans, onions, carbonated drinks), high-fat diets. Identify personal triggers via “food-symptom” diaries for targeted avoidance.

- Lifestyle: Maintain a good psychological state (avoid long-term stress), regular work-rest schedule, appropriate exercise (e.g., walking, yoga).

- Regular Follow-up: Patients with frequent symptoms should seek regular medical care and adjust treatment plans.

Research Progress

(1) Pathophysiological Mechanism Research

- Brain-Gut Axis & Comorbidities: IBS is often comorbid with chronic pain disorders like fibromyalgia, linked to abnormal sensory signal processing in the brain and disrupted brain-gut signaling. About 30%-50% of patients have concomitant anxiety/depression, forming an “emotion-gut” vicious cycle.

- Gut Microbial Metabolites: Metabolites like SCFAs and bile acid derivatives affect gut barrier function, motility, and immune response. However, there is currently a lack of systematic integration of “microbial metabolites – gut-brain” pathways, necessitating clarification of key directions with bibliometric analysis.

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): Forms a vicious cycle with IBS (SIBO worsens IBS symptoms, gut dysmotility leads to SIBO). Eradicating SIBO (antibiotics/diet modification) may be an adjuvant treatment strategy.

(2) Treatment Advances - Microbial Intervention: Multi-strain probiotics combined with vitamin D improve gut barrier function (increase mucus secretion, reduce inflammatory factors) and modulate gut microbiota in non-constipated IBS patients.

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Reconstructs gut microbiome by transplanting fecal microbiota from healthy donors to improve IBS symptoms. However, issues like “optimal donor selection” and “administration route (oral vs. colonoscopy)” need addressing.

- Personalized Diet: Long-term studies on low-FODMAP diets show about 60% symptom control rate in patients receiving dietary education (higher than those without). Future exploration of “personalized FODMAP” diets (adjusting restrictions based on individual microbiota) is needed.

- Psychological Intervention: Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) training – 15 minutes daily for 6 weeks can reduce symptom severity by 30% and improve quality of life by 25% in patients with concomitant anxiety.

(3) Challenges & Future Directions - Research Challenges:

- Difficulty in precise subtyping (lack of biomarkers to differentiate subtypes).

- Lack of treatment efficacy prediction models (inability to accurately predict patient response to drugs/interventions).

- Insufficient long-term follow-up data (most studies are short-term; ≥5-year follow-up data is rare).

- Future Directions:

- Precision Medicine: Using multi-omics (genomics, metabolomics) to find biomarkers and achieve personalized treatment.

- Brain-Gut Axis Targeted Therapy: Developing new drugs modulating brain-gut signaling (e.g., endorphin modulators).

- FMT Optimization: Screening for “super-donors” (via metagenomic sequencing), exploring oral FMT capsules (improving compliance).

- Long-term Outcome Studies: Conducting large-scale, multicenter, long-term follow-up to clarify long-term effects of treatment strategies.

Resources & Further Reading

1. Major Medical Organizations & Foundations:

- International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders (IFFGD): A leading source for patient education and advocacy. https://iffgd.org/gi-disorders/ibs/

- American College of Gastroenterology (ACG): Provides patient-centered resources and clinical guidelines. https://gi.org/topics/irritable-bowel-syndrome/

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK – USA): Authoritative, science-based information. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome

- National Health Service (NHS – UK): Reliable, practical health information. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs/

- Mayo Clinic: Comprehensive overview of symptoms, causes, and treatments. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20360016

2. Dietary Management (Key Resource for Low FODMAP Diet):

- Monash University FODMAP Diet: The creators and leading researchers of the low FODMAP diet. Their app and website are considered the gold standard. https://www.monashfodmap.com/

3. For Research & Scientific Literature:

- PubMed: Search for the latest clinical studies and review articles. Use keywords like “Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” “IBS pathophysiology,” “gut microbiome IBS,” “brain-gut axis.” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- Rome Foundation: The organization that establishes the diagnostic criteria (Rome IV) for functional GI disorders like IBS. Their site provides access to criteria and educational materials. https://theromefoundation.org/